In 2019 SAW released a publication. The publication was the outcome of many months of self reflection and careful consideration, within it’s pages we sought to explore and explain what SAW is, what it has been, and what it aims to be as an organisation. There are several essays within it that explore different aspects of our thinking and practise- here is one of them.

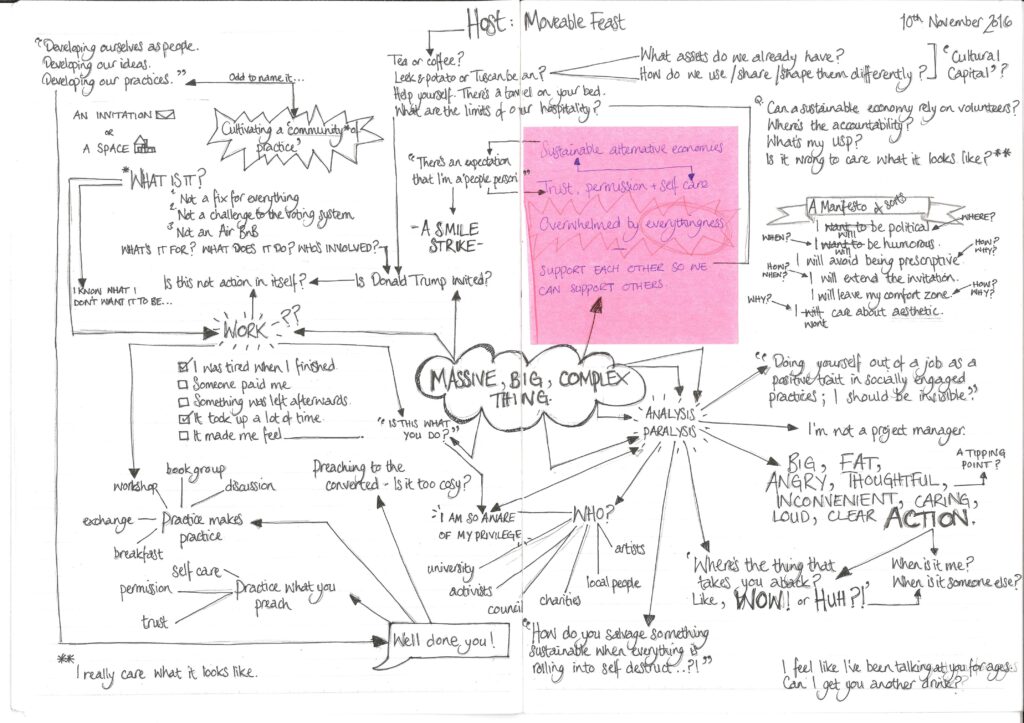

Part of HOST, Moveable Feast was a travelling encounter with five individual but connected practices to instigate wider discussion, questioning and critique on the role of hospitality in socially engaged art. In this essay, Sophie Hope reflects on her experience of the day.

Starting from a warm living room with coffee, then walking (but not in a big group) with the pushchair to another home via a stop-off at a charity shop (bought a hat). Standing in a cold shed on a city farm and then onwards to sit on sofas in a gallery for more tea and chat. The pace is slow, there is plenty of food and drink to keep us going. We are in a constant state of listening and/or talking. There is time to get to know one another and the work that is being done around us. We start by asking, ‘why did you give up today to be here’?

I would be sat at a desk otherwise / To be with you guys / To support friends / To meet new people / Because I’m feeling quite hopeless / Because it connects to what I do / Because I helped organise it / To speak about important matters / To reflect on practice / Because this is my house / It’s a life line / This is my PhD day / To dig down deeper / Because I’m intrigued / It’s a day offline

As we talk, something that strikes me is the recurring theme of the relationship between life and/as work – the ethical and moral positions people take in order to operate as citizens/neighbours/artists/curators. There are no easy lines to be drawn around ‘the job’ and being a member of a community (where does this job begin and end?). The job I think we are talking about here is ‘citizen artist’. By taking a public role (as a local Councillor, GP, vicar or community activist might), something of one’s private sphere is given over to the public. One’s house is not entirely one’s own, people come and go. You get stopped in the street, asked questions, you’re actively involved somehow in parts of the life of the community. This separation between leisure and work is often challenged during parenthood. The work of women, often as primary carers, is not easy to clock in and out of, we are constantly on call. The home and its immediate surroundings become the workplace that we are wholly committed to, leaving very little time and space for oneself.

On our peripatetic group crit a number of characteristics of the citizen artist emerge (a profile that is held in tension within these bodies I walk alongside):

I’m a public citizen. This means I care about the people and places I work with, at home and away. I’m usually on call for conversations, coffee and various meetings.

I’m good at applying my skills in aesthetic form to whatever we do together. Please give me room to do this.

I like to figure things out as I go along, so don’t expect to know what will happen before hand.

I’m an emotional decision-maker and likely to change my mind. But my politics can be strong.

I commit long-term to a place and the people here. I’m not just in it for the money, although often it runs out and I have to move on, sometimes I stay. Either way, this makes me feel uncomfortable.

I’m the one who asks stupid questions so you don’t have to.

I like to provide an alternative voice when the chorus seems too united.

I have a particular skill in bringing people who don’t usually talk to each other together around the table and get them to listen to each other and find solutions.

But I can’t fix things for you.

There are health and financial implications of living this way and so it might not be an option for everyone (Is it a choice? Can you afford it?). Giving up some of your own private space (head, home), implies there is less time/space for you/your family. Perhaps there is a growing sense of obligation/responsibility that you have to keep on providing a (welcoming) space for others. When your job is on your doorstep, creeping into your home, it might feel there is no escape. Sometimes you might want to shut the door, wear a disguise and not be that citizen artist today.

But maybe this is the wrong way of looking at it. Maybe the citizen artist is not one figure but a complex web of co-relations, co-dependency and mutual aid. In this sense, hospitality is not a two-way relationship. Forget about hosting, it’s about multiple, messy exchanges. There is always a politics and power-relations to these exchanges and encounters. There is an awareness of who is engaging, and on what (whose) terms. There is a cost (time, money, health) to any act of exchange. They are loaded with expectations and never neutral. How, then, can these exchanges be thoughtful, honest and radically open (i.e. not just open to others who look like / think like me)? How do we acknowledge, prepare for and share the invisible labour that public citizenry entails? And what are the implications of privatising (charging for) this role? Which aesthetic forms emerge from these encounters of being in a place?

These questions are informing the decisions we make as ‘citizen artists’, a label that implies we choose to be connected, through our actions, to the places we land and live. The details of the role(s) we play in these conditions is context-specific and can morph and change, chameleon-like. There might be a tension between playing that role, consciously getting into character, in a way that protects a part of oneself for when you’re off duty, and wanting to engage your whole body and soul to the role. Acknowledging the burn-out rate of people who over-commit, however, could we think of ways of safeguarding the physical and mental health of ourselves and those we work with? Identifying what the roles are and the type of physical and mental labour they entail (giving them labels and limits), might help us understand the work better and sustain it in a healthier way. This is not to deny one’s commitment to the job, but to give it a clarity that might help us step in and out of these roles with less tired bodies. I have found this with my daughter (who has a disability) – I am learning to go from being playmate, to amateur physiotherapist, to being her personal assistant organising her health appointments. These are the jobs I am doing, that I can perform in chunks of time. I am learning by doing, which is often messy, unstructured, and full of mistakes, but getting to know these are the roles (which I can share, outsource etc) is empowering for me as it doesn’t seem so daunting or all encompassing. These roles support each other and act as a patchwork of activity throughout the day. Similarly, with the jobs of hospitality that we discussed during Moveable Feast, such as listening, curating, facilitating, organising – each approach has its discrete characteristics, but they can be recognised as particular roles.

It may seem formulaic to compartmentalise and prescribe job roles to art practices that are embedded in the everyday, but it is this push and pull of art as/in everyday life that, I believe, we were struggling to maintain and justify. By treating and naming aspects of (motherhood and) artistic practice as jobs, we can start to treat these elements as work and see what they are made of. We can start to acknowledge that there are certain conditions needed to carry them out. It might then be possible to put them to one side, step out of role, hand on or share the role. This may also mean we are able to create time and space where we are not defined by that role. The limits of the labour of hospitality are ours to define (perhaps collectively) but without limits, there is a danger of burn-out and general frustrated feelings of being pulled in different directions and, bizarrely, not feeling we are committed enough!

Dr Sophie Hope, a practice-based researcher and lecturer in Arts Management at Birkbeck, University of London